아티스트

-

Untitled Document Maelee Lee: Infinite Space

Dr. Thalia Vrachopoulos

Thalia Vrachopoulos is Ph.D. International Art Critic, Curator,

and Professor in Jonh Jay College of Criminal Justice City University of New York.Although Maelee Lee’s works for the Chelsea Art Museum show take on three morphologies, they all examine conceptions of space. Space takes on different forms depending on the area of cognition; mathematics, psychology, mechanics, philosophy, and personal. It is demonstrated in Lee’s photographs as atmosphere, negative space, or artistic or infinite space. Lee’s works are photographic conceptual installations that consider their in-situ environment or the gallery space for which they were made. As such they are minimalist works with photography as medium but whose primary concern is the concept.

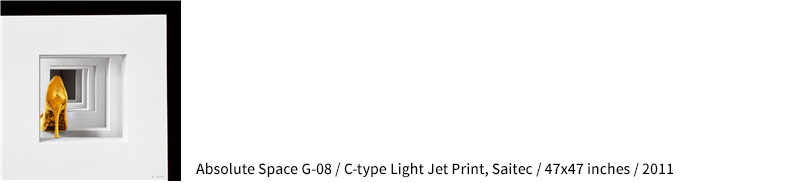

The first series entitled Absolute Space, 2011 tackles the issues of time and space, being and existence. Visible substance takes on the form of a woman’s high heel pump, a mountain or the sea. The high heel pump is the symbol of feminine manifestation. Lee’s sculptural pieces appear as white boxy forms that are multiplied through actual planes in space as well as through mirrors with the high heel shoe that adds another dimension to their reading. Although Isaac Newton’s Principia (1687) refers to absolute space as a background space for mathematics, Lee’s conception is more like the infinite space of the N-dimension. In optics photography it is not only the axial or direct but also the oblique rays that must be brought into focus. This is analogous to Lee’s multiplication of planes through the use of mirrors and/or framing devices.

Lee’s 2010 Ocean series photographs are also about space, one that is solid and alternately void; the observed and the invisible. The solid/void relationship holds great significance for Korean culture, and is associated with the yin and yang or feminine and masculine principles of Taoism. In this context also the void is full and empty simultaneously. Lee has physically sliced the photographs of the ocean taken during different weather conditions so that she exhibits the piece in horizontal slats read as solid and void that like Carl Andre’s minimalist sculptures are meant to sit partially on the floor. Andre is known as one of the artists who established Minimalism, an art style that reduces the artistic components to their purest level of precision, austerity and tranquility.

Lee’s Poetics of Space, 2011 photographic series depicts land-seascapes overlain with textual references. To Lee substance is represented by ocean/landscape while the text contains worlds of a different time and space. So that, when Lee alludes to Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, it is understood that she means to include this author’s own time and place. In the essay Woolf postulates for women’s right to have a space of their own in which to be creative and the means with which to support themselves. Lee also employs text from Heo Nanseiolheon who wrote poetry in Korea during the 16th Century Chosun Dynasty. In Kyunwonka Heo petitions female acknowledgment and writes about the unrequited longing of women for recognition. Woolf’s writings like Heo’s advocate women’s independence and as such reach outside their own time and space to be relevant even to our own era. Perhaps these two heroines didn’t live to see their independence during their own era but by inscribing the landscape with their texts Lee is claiming this space for them.

Taken as a whole, the exhibition can be seen as the juxtaposition of Euclidean geometry (parallel rectilinear lines) and non-Euclidean (spherical and hyperbolic geometry) space. While the severe grid-like forms of the Absolute Space works are Euclidean, the softer round lines of the high heel pumps are non-Euclidean. Consequently Lee examines both ancient Greek geometry, Asian philosophy and modern philosophical precepts of space as they pertain to woman-ist thought. -

Untitled Document Maelee Lee: Walking the Truth

Dr. Thalia Vrachopoulos

Thalia Vrachopoulos is Ph.D. International Art Critic, Curator,

and Professor in Jonh Jay College of Criminal Justice City University of New York.

Maelee Lee’s high heel pumps speak volumes, but her installations’ circumambulation pattern is notable as well. This meditative journey in the round that inspired Lee, is an integral part of Hinduism and Buddhism. This pariyahindana is usually circular as you are meant to walk around a dagoba or stupa and twirl the prayer wheels while doing so. This idea of circumambulating a holy center is also prevalent in Christianity and Judaism, while in the Islamic tradition one circumnavigates around the Q’abba. However, because Lee is from Korea it is most likely Son Buddhism that informs this body of work. This perambulation is called kinhin and in Korean Haengseon which is a walking technique focused on the present and practiced in between long sitting meditations. The practitioner holds a shashu mudra with one fist in his other hand, and breathes deeply after which he takes a step walking in as clockwise pattern around the room. This is a type of walking in synchrony to the Son teachings or walking the truth of the sutras and is meant to make one alert of mind and calm of body.

The pattern of Lee’s installation can also be related to the Neolithic signs for the mother goddess, the cycle of birth and seen as a symbolic womb. These spirals are primal signs of the unrestricted forces of nature; the universe, and lunar, seasonal, and solar patterns. This is also a symbol of progression and change, of movement and development rather than stationary. Lee’s chosen spiral pattern carries a positive significance and has existed in the arts of many cultures. In Celtic designs, in rock carvings, in Nazca earth sculptures, Arabic architecture, African art, and aboriginal paintings. In fact, it is an archetypical sign that is non-sectarian seen by most to representing the cycle of/or entryway to life.

Lee uses the spiral as a sign for the journey of life and as a way of alluding to the endless discovery undertaken as walking meditation. But, she uses high heel pumps made of paper as a way of overturning their utilitarian value but also to make a statement about life’s journey. The heels are signs of feminine beauty and sexuality, but combined with the journey and because of their height, they become objects of penance. Doing penance is commonly undertaken in religious practice where it absolves sins bringing about a reconciliation of faith. Because she utilizes high heels in her works since 2005, the element becomes a fetishist symbol that can be interpreted as the reason for doing penance as seen in the latest works of 2015. Lee has installed the high heel shoes in bamboo forests, in modern buildings, in the countryside, or forming walking patterns on mountains. By so doing, she is making a statement about a spiritual journey that is likened to the Son walking meditations.

Lee makes her high heel shoes from recycled paper which is not a permanent material thus she overturns the reading of a shoe’s ability to hold up the person’s weight. Furthermore, she makes works that are monumental like the Red Heel, a startling format for a woman. In this case, it could be said that she’s claiming autonomy which is difficult in Confucianist Korea, at the same time as she is asserting her femininity. Although the heels are seen as feminine signs, they are not feminist per se for even Gloria Steinem threw off the ‘yoke of feminine trappings’ when she got rid of her bra. Dichotomies such as these, in Lee’s art formulate her works’ multi-leveled complex fabric and subsequently its readings that add viewer interest. -

Untitled Document Maelee Lee Feminine and Strong

Dr. Thalia Vrachopoulos(Dr. Thalia Vrachopoulos is Ph.D. International Art Critic, Curator, and Professor in John Jay College of Criminal Justice City University of New York.)

Maelee Lee's recent work comprises photography, video and sculptural installations in a post-minimalist style that embraces simplicity yet has multi-dimensional content. These media link Lee to the Post-minimalists who in their anti-formalist enterprise sought to redefine art adopting an anti-painting stance. video projection or sculpture Lee's focus remains conceptual as the real substance of her work. While Minimalists like Judd and Serra in their embrace of purist aesthetics declared painting dead for its inability to be a literal sculpture object without reference to the real world, Lee plays with space rendering it illusionistic thus is antithetical to their enterprise. They are literal objects of sculpture being photographs.

And it is precisely because of these references to the real world that Lee's photographs are not like the sterile silent cubes of the minimalists, but are warm and inviting. Lee has revitalized art by reintegrating it into life creating such sculptures as her Gold and Silver Pumps shown in conjunction with her photographs. The artist explores the visual process by creating perceptual ambiguity so that when looking at her installations one can never really be sure of their spatial relationship to their surroundings. This constant questioning of viewed space results in ambivalence that maintains retinal dynamics. So that, Lee's work cannot so easily be placed into any one particular category or style. Her purist rendering of space is like Judd's as is her multiplication of objects. Do these tendencies make Lee a Minimalist? And, Lee's engagement with spatial ambiguity relates her work to Op Art. One thing for sure, conceptually Lee is close to the minimalist So Le Witt who in 1965 wrote "the idea of concept is the most important aspect of the work.... The idea becomes the machine that makes the art."

In conceptualism documenting the idea is crucial for only in conveying it to the viewer while reserving it for posterity can the transformation it seeks take place. Processing through the post-industrial media of photography Lee is provided with the means to document her ideas as part of the post-modernist enterprise. Lee salvages not only the artwork but also its "aura" as Walter Benjamin called the artwork's uniqueness, via sub-textual analysis and discourse. -

Untitled Document Maelee Lee: On the Road to Wisdom

By Richard Vine

A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. So runs the old Chinese adage that seems to hover in the background of Maelee Lee’s new multi-site project in Korea. Her work has always, to a certain extent, been about travel — mental as much as physical, though time as well as space. But what was previously a generalized, abstract meditation on the self in transit from one locale, and one state of being, to the next has now planted its feet firmly on the earth, so to speak, grounding the viewer’s experience in a specific cultural history: the intellectual heritage of Jeong Yak-yong (1762-1836), an esteemed Joseon Dynasty poet, scholar, civic administrator, royal adviser, and philosopher.

At first glance, this might seem an unlikely choice for Lee. Holding an MFA and a PhD in fine arts from Chosan University in Gwangju, the artist has, over the last 15 years, developed a distinctly contemporary style. Creating small sculptural vignettes and large-scale installations — most of them involving at least one high heel shoe that serves as her personal surrogate — Lee then photographs and/or videotapes the ensemble, thereby vastly increasing the potential reach and distribution speed of her work but also problematizing its nature. Is her art the object or the image, the assemblage or the idea? Perhaps it is both at once, an aesthetic composite that parallels the psychological dualism of her theme: a woman contemplating her own social and psychic construction as a woman.

This ontological conundrum is, of course, not unique to Lee. One encounters it, in a recent and more blatant form, in the dress-up fantasies of Cindy Sherman. Moreover, the “what is the work?” debate runs back through Conceptualism to that movement’s fountainhead, Marcel Duchamp, and farther still into the reaches of history. It connects to the Platonic dichotomy of material form vs. Ideal Form and even to the primitive distinction between the ritual object and the spirit that inhabits it, the idol and the god.

Little wonder, then, that Lee has made the evocation of infinite regression one of her most fruitful devices. In her “Absolute Space” series (2011), she variously juxtaposes three elements: a high heel shoe, a box structure with multiple concentric window-like cutouts, and — beyond the last aperture — an open book. The viewer, reminded how various frames of reference alter perception and meaning, is simultaneously drawn inward, deep into the text and the private domain of interpretation, and propelled outward toward the social sphere of high fashion footwear.

To step in or step out? This is the dilemma faced by every modern woman and by every artist (who, as Thomas Mann so memorably put it, must repeatedly choose between immersing oneself in everyday life or turning one’s back on reality in order to produce the art that reflects and immortalizes it). In Lee’s 2011 series of painted photographs “Between Real and Ideic Space,” seascapes and distant mountains, both common symbols of departure and contemplation, are combined with mutely toned rectangles and passages of printed text — filters that are placed immediately before one’s eyes but can nonetheless, like traditional Eastern screens bearing wistful painted scenes, offer imaginative passageways to the viewer’s interior.

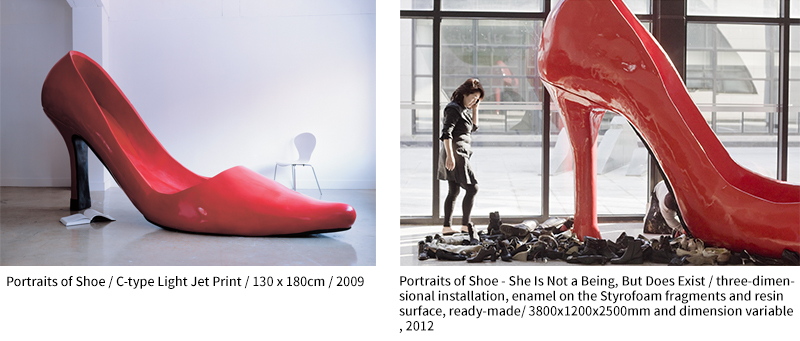

Lee’s use of the high heel shoe — in “pure” white, avaricious gold, or brashly sexy red — is often seen as an assertion of female identity and power, especially when, in instances like Portrait of a Shoe (2009), the object assumes giant, Claes Oldenburg-esque proportions. One should note, however, that it is only the habitually oppressed or ignored who need to proclaim their presence in such an insistent manner. (Thus, for example, the desperate swagger of hip-hop.)

Lee’s art lies as much in pinpointing the continued subjugation of women (still widespread, though grown more subtle) as it does in providing a confidence-building social response. Yes, Lee seizes the high heel fetish, making it her own — thereby “owning” it rather than being owned by it — but that very gesture of appropriation bespeaks an ongoing chauvinism that is yet to be broken.

This may be the key to the artist’s new itinerate, multi-location work “Road Project: From Dasan Chodang to the Korean National Assembly” (2014). During a residency earlier this year at the Siena Art Institute, Lee produced from recycled paper (another allusion to the social status of women) scores of white high heel shoes, some of them with naturalistic toes that meld the sartorial object (a cultural product) with the fleshly foot it enhances and protects. These shoes she then installed — and sequentially photographed — in a number of different arrangements at historically freighted sites throughout the old Italian city.

In May 2014, Lee will do likewise in her native country, tracing an itinerary from Dasan Chodang, the simple house that Jeong Yak-yong occupied in the provincial southwest during an 18-year banishment from the center of government, to the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea, in present-day Seoul. Given that Jeong Yak-yong (also known as Dasan) was a prolific Aristotle-like polymath, Lee’s project is, in effect, a journey from a seat of wisdom to a seat of power.

The stops will be determined as the process evolves, but some of the primary targets are: the road between Dasan Chodang and Baekryeon Temple, home to Dasan’s great friend, the venerable Buddhist monk Hye Jang; the lecture room of the Confucian scholar Gi Dae-Seung (1527-1572), whose work was a great influence on Dasan; and the tomb of King Jeongjo, whom Dasan served before the monarch’s death in 1800.

Lee’s “Road Project” suggests, then, that Jeong Yak-yong’s “practical” philosophy — based on fundamental Confucianism, tinged with Christian values, respectful of longstanding rituals, and much concerned with personal comportment, good governance, and the amelioration of poverty — should ideally migrate from the distant past to the contentious present. Thus would it carry the issue of female identity, and many other pressing moral concerns, from the realm of theory to the arena of pragmatic laws and public behavior, from a sage’s former hermitage to the nation’s active legislature.

-

Untitled Document Lee Mae Lee:

New Variations on Minimal and Architectonic ArtRobert C. Morgan

Lee Mae Lee is interested in video and in Minimal architectonic forms. She uses the surface of modular, stacked plywood boxes as a screen on which to project video images. Her projections began three years ago with close-up images of earth and rock, which eventually led to the use of systemically repeated words (in English) such as “communication.” In the latter case, the word appears in several permutations as a word-block, always projected against the surface of a slightly uneven stack of plywood boxes. Sometimes the word-block will move sideways, then diagonally, and sometimes up and down. Unexpectedly, a projected image of a high-heeled shoe may tumble through the words as if to break-up the monotony and surprise the viewer.

In these Minimal constructions, Lee Mae Lee is not simply giving the viewer a visual exercise. Rather she is elucidating the possibility of a new kind of symbolic code through the use of Minimal form and architectonic imagery. Her stacked Minimal boxes covered with digital light suggest a hybrid between language and image, or a gap between the Informational Age and the material fetish. Her appropriation of Minimal art and video (DVD projection) further suggests a kind of installation art. Kinetic movement accompanies the static placement of architecture, just as the neutral dimension of information may suggest the sublimation of Eros.

One can trace this work by Lee. Mae Lee back to an earlier work on plywood called “Land for Drawing” from 2001. It is a simple Minimal work in which a quadrant of four squares is laminated against a larger horizontal rectangular sheet of plywood. The surface is painted a uniform color with dribbles of paint in the style of American “action painting.” In addition, there is an indeterminate series of roughly etched marks and incised lines cut into the surface that function semiotically as a visual complement to the dribbles of paint. The paint and the etched marks interact metonymically on the same level, and thereby, intensify one another. At the outset, Lee Mae Lee understood “Land of Drawing” in terms of painting, but eventually this flat planar work became a passage towards something else -- a transition from painting to sculpture. It was here that Lee Mae Lee quickly perceived the possibility of working not only in three-dimensional space, but also with time.

Since 2005, the artist has been involved in a new series of work – another application of Minimal architectonic form – through the use of painted aluminum panels. Entitled “Unconscious,” these works may include a diagonal panel, painted in a different color, inserted over the top or wrapped around the sides of three vertical aluminum-painted panels. In one case, the work functions in direct relation to architectural space as two panels are placed next to a third on an adjacent wall. In another version, a triptych is accompanied by a diagonal ramp on the right side with a group of cast high-heeled shoes descending towards the triptych. The absurd humor of this piece holds a certain irony, as signs of the secular and sacred world seem to collide upon one another.

In each of these groups of work, Lee Mae Lee is searching to extend the application of Minimal art through a broadening of its vocabulary. She is giving Minimal art another context for viewing and another possibility for interpretation. The use of an architectonic context in her work suggests that the artist is thinking of form not only in terms of meaning and deconstruction but also in terms of transition between art and architecture. While interested in decoding certain assumptions about Minimal art regarding its male gender specificity, she is also deconstructing the logotypical relationship of Minimal art to corporate globalism. On this level, Lee Mae Lee appears to be questioning the very foundation of art’s ability to communicate beyond the marketplace of signs.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Robert C. Morgan, Ph.D. resides in New York where he functions as an art historian, curator, artist, and international art critic. In the Fall 2005, he was a Fulbright fellow at Chosen University. His book, “Art into Ideas” (Cambridge University Press), is being translated and updated into a Korean edition, available in late 2007. -

Untitled Document Female Identity and Timeless Space in Maelee Lee’s Work.

Maurizio Bortolotti

(Curator of Zuecca Project Space International Program)

The starting point of Le Mae Lee’s work is the use of architectural minimalistic form, but she doesn’t take inspiration from the American art movement. Her work is much more oriented toward a representation of a feeling of life. As she says: “I try to express the feeling of existence through

three-dimension space”.

The use of minimalistic form was developed in her work as a space-time representation, in which time and space blurred into each other. In her painting “Time’s Being Space”, 2001, the artist places a square representing an essential image of space inside another space. This space inside hints at a development of time dimensionality. In another later work, “Drawing for Earth”, 2003, the artist goes directly into three-dimensions. Here the two-dimensional image is developed in real space making a cubic shape installed in a room.

In “Space-Zero” (2007), the artist employs a series of stainless steel panels that symbolize elements like sky, ground, and sea, blurred together. This is an essential form of representation in which space and time are fused in a contemplative feeling of life and become one. Lee Mae Lee’s search for a symbolic representation of space-time refers to her anthropological background of culture in her homeland, Korea.

However, the turning point in her work is the introduction of the image of the female shoe. Starting from this moment, it becomes the fundamental icon of her work. The use of this image allows Lee to enter the everyday life space. Inside all her work there is a subtle process of symbolization, even the image of shoe is taken as it and not simply as a quotation from reality.

The artist believes the shoe is her own Alter Ego. She takes it as a starting point to explore a female public identity, transforming it into a personal obsessive feminine image.

The shoe’s red color and high heel offers an image of today life style, a social female ideal. It is a idol of modernity as symbol of desire and consumerism in a society devoted to consume; but it is also a representation of fugacity of life summed up in an icon. It is an female image, connected to a traditional idea of female role assigned by fashion and spread by media in society. So, Lee uses this image as representation of a social relationship, as it relates to the roots of Modern Korean society.

Nevertheless, her concern about space/time takes the image of the shoe far beyond of a female icon. This object, the shoe, becomes a representation of an existential condition, in which its link to desire and seduction turns to be a representation of feeling of life. As it is a representation of social status, the shoe becomes a medium of communication.

This is evident in “Communication and Desire”, 2004; or in the series “Communication, Communication; Communication” realized in different versions from 2007 to 2008. This minimalist structure together with the image of the shoe implies the idea of deconstruction in which minimalism becomes a representation of sentiment of life. In these works the writing “communication”, obsessively repeated, is an essential idea of contemporary society. It is a kind of spectacle.

This development in her work appears in her 2007 series “Time’s Being Space”. In these installations the grid of minimalist architecture overlaps the everyday presentation of a shoe in a bookcase. The universalism of minimalist sculpture enters the precarious instant of everyday life as represented by the shelf/bookcase.

In works, such as “Portraits of Shoe” (2009); “The Glimpses of Life” (2012); “Into the Great Silence” (2013) she articulates the idol of shoe in many different aspects, but in all of them there is the idea to explore a social idol in search of a representation of contemporary society. The iconic structure of “Into the Great Silence”, made the shoes in recycled paper, looks like a shrine and a symbolic image of our society in its pyramidal structure.

The image of shoe becomes a medium with different levels of meaning. It represents the female condition in contemporary society but also a precarious feeling of existence. The object becomes the protagonist of Lee’s work with a strong symbolic dimension granted by the artist.

In her work shoe is not simply an object to show, it becomes a witness to present life: the “Simulacre" of the artist watching the world. An installation from 2011, a shoe three meters high, was placed in front of a container covered by graffiti. Or in “Portrait of Shoe”, 2013, when it is installed outdoor, nearby a structure with mirrored surface reflecting the city in front of it.

This is more explicit in the series “Absolute Space”, 2011, where a shoe is photographed in front of framed fragment of a book. This is a clear representation of an idea of witness. The artist’s object of desire observes fragments of art and literature told in a book, on which some lines are isolated. The absolute space here is that of memory and time. The work, even due to the process of photographing it becomes an abstract space on which a narrative time is told. In some of the works from this series the shoe enters this space and becomes gold, the space of memory.

What Lee does in her compositions is not to build a new iconography. On the contrary, she is exploring an “everyday mythology” in which to criticize Korean traditional society by focusing on female identity as conventionally received within it. The shoe is the mark of her work as an artist dealing with social criticism.

In her recent works from 2014, Lee has realized a series of site specific installations in historical sites in Tuscany and Korea. Here the shoes change from a gigantic industrial product painted in red to a group of smaller recycled paper. As she has written: “The image of shoes in my early work presents my alter ego, the images of shoes in the recent installation present anonymous people.”

In these works she arranges a series of shoes in patterns interacting with ancien architecture and historical locations in Tuscany, revealing again her strong interest in architecture. She covers the ground of a courtyard of shoes following a precise pattern of concentric circles, till the base of an old well. another installation is to arrange shoes in subsequent rows above the steps of a church in San Giminiano. Her work suggests a confrontation with religion. In South Korea the artist makes an installation inside a sacred site, establishing a dialogue between a temple, with the symbol of Yin-Yang painted on the door, with her shoes organized in geometrical patterns. In other installations she distributes her shoes in different spots inside the sacred area. The shoes are organized following patterns to which she gave an harmonic organization. The “absolute space” is not anymore the space of memory, but that of spirituality, the Italian church and the Korean temple.

The shoes in recycled paper represent the people. The confrontation with religion and the social relations puts her again at the center overf controservy. What she seems to develop here is a research about the inner values of a community, looking for a more authentic and pure ones. -

Untitled Document ‘우리는 어디에서 와서 어디로 가는가?’ -상실의 시대, 자아성찰을 통한 치유의 메세지

김희랑 광주시립미술관 학예연구사

이매리의 <Portraits of Shoe-우리는 어디에서 와서 어디로 가는가?>전은 수많은 하이힐을 쌓아 올린 작품이 없었더라면, 이매리라는 작가와 쉽게 연관 짓기 어려운 전시였다. 그러나 그동안 사진, 회화, 영상, 설치 등 끊임없이 다양한 실험과 시도를 행해 왔던 그녀의 작업과정을 지켜보았다면 그리 낯선 것만은 아닐 수도 있다.

과거 이매리는 미니멀한 공간에 놓여 진 하이힐을 통해 존재와 부존재, 유와 무, 공간과 시간의 개념을 보여주었다. 흔히 그녀를 후기 미니멀리즘 경향의 작가로 인식하는 경우가 많다. 그러나 이매리는 물질성과 기술 그리고 스타일을 강조하는 서구의 후기 미니멀리즘과는 달리 열망이나 사유와 같은 정신적인 것과 인간적인 감성을 담아냈다는 점에서 차별성을 보여주었다. 어찌되었건 과거 이매리의 작품이 개념 보다는 시각적 조형성에 많은 무게를 두었고, 개념적 스토리는 미니멀한 형식 뒤편에 내재되어 있었던 것이 사실이다. 그러나 이번 전시에서는 작가의 사유와 발언이 더욱 구체적이고 직접적인 언어로 전면에 등장하게 된 점이 가장 눈에 띄는 대목이다. 이매리는 이번 전시를 통해 지적 조형적 산물로서 작품 활동보다 성찰적 철학적 도구로서 작품 활동으로 방향 전환을 꾀하고 있다. 지금까지 이매리는 작가로서 앞만 보고 달려왔다면, 이번 전시를 통해 자신을 돌아보고 자신의 삶과 실체적 존재가 녹아든 예술의 세계로 진입을 시도하고 있다.

이번 전시에서는 하이힐뿐만 아니라 부모의 고향 강진을 지키고 있는 대나무 숲과 월남사지석탑을 영상작업으로 옮겨온 작품과, 자신의 조상들의 이름을 적은 지방(紙榜)을 사용한 작품이 함께 선보였다. 그러나 역시 그녀 작업의 실마리를 ‘하이힐’에서 찾아보기로 한다.

이매리 작품에서 2000년대 중반 등장하게 된 하이힐은 성적 상징물-특히 여성성-로 읽혀져 왔다. 신발이 갖는 전통적 상징성이 너무 강력한데다 여성작가이고, 그 형태가 하이힐인데다 너무도 선명하고 자극적인 빨강색이기에 더욱 여성의 성적 상징물로 비춰졌다. 물론 필자 또한 그러한 의견에 동의한다. 그러나 이매리의 하이힐은 단순한 여성의 성적 상징물로서 한정시키기 보다는 작가자신의 존재성을 드러내는 사물이라는 해석이 더욱 정확할 것이다. 나아가 형식적 굴레, 즉 전통적인 가치관에 의해 형성되어왔던 규범과 질서에 의해 규정지어진 정치적 사회적 메커니즘으로부터 소외받은 타자들의 자화상이라 할 수 있다. 에로틱한 빨강색과 거대한 크기의 하이힐은 화려함과 위압감으로 무장하고 제도권 혹은 권력의 중심으로 진입하고픈 타자의 욕망을 대변해 주고 있다. 이러한 가면을 쓰고 있던 하이힐이 최근 그 옷을 벗어던지고 부서지기 쉬운 유약한 종이죽으로 만든 무색의 하이힐로 변화하였다. 이는 생물학적 신체적 의미의 성, 즉 섹스(Sex)의 개념이 아닌 사회 문화적 의미의 성, 젠더(Gender)임을 분명하게 밝히고자 하는 의도가 담겨있다. 과거 빨갛고 공업용 재료로 무장했던 하이힐이 이제 무색의 유연한 재료로 바뀌었다는 것은 나약하고 인간적인 타자로서의 본질을 드러내려는 시도이다. 욕망과 가식을 벗어나 자기존재를 있는 그대로 인정함으로써 그 본질을 직접적으로 제시하고, 스스로를 위로하고 치유하려는 의도이기도 하다.

지난 9월 광주시립미술관 <만물상-사물에서 존재로>전에서 보여준 이매리의 작품은 지금까지의 형식을 완전히 탈피하였다. 유럽의 로톤다(Rotunde) 건축양식을 차용하여 만든 구조물 위에 무색의 하이힐을 쌓아올린 작품으로 사회적 정치적 불합리하고 부조리한 시스템의 틈바구니에서 희생당한 억울한 자들에 대한 진혼의 의미를 지니는 작품이었다. 그 후 이번 전시에서는 건축적 구조물이라는 형식마저 거부한 채 수많은 하이힐을 무작위로 쌓아올린 형태를 보여주고 있다. 보는 이에 따라 석탑 혹은 돌탑과 같은 형상이라고 하지만 필자는 타자의 희생을 상징하는 무덤을 연상하였다.

지금까지 언급한 바와 같이 이매리는 ‘하이힐’을 통해 수년 동안 자기 존재와 실존의 문제에 대한 고민을 거듭해 왔다. 이번 전시에서는 그 문제를 자전적 소재를 통해 더욱 진솔하게 풀어냈다고 할 수 있다. 영상작품 ‘우리는 어디서 와서 어디로 가는가? Ⅰ·Ⅱ’에는 부모의 고향인 강진의 대나무 숲, 월남사지 삼층석탑과 제사의식에서 사용되는 조상의 이름을 적은 지방(紙榜) 등 실재적(實在的) 공간과 실재적 사물이 등장한다. 자기 존재의 근원을 찾기 위한 방법으로서 고향, 조상, 가족이라는 자신의 뿌리와 관계된 것들의 의미와 그것들과 자신과의 관계에 관한 성찰을 보여주는 작품이다. 자기 존재에 관한 고민은 자신을 존재하게 한 고향-특정 장소로서 대나무 숲과 월남사지 삼층석탑-과 조상 등 생태적 환경적 유전자에 대한 관심으로 확장되었다. 또한 자신의 자전적 이야기는 영혼 없이 껍데기 상태로 살아가는 현대인들과 인류의 문제로까지 확대될 여지를 남겨준다.

‘우리는 어디서 와서 어디로 가는가?’

삶에 대해 한번쯤 고민해 본 사람이라면 떠 올려 봄직한 말이다. 하지만 세상일에 치여서, 먹고살기 힘들어서 혹은 먹고 살만하니까 잊어버리고 사는 말이기도 하다. 인간에게 가장 중요한 숙제는 ‘어떻게 살 것인가?’ 혹은 ‘무엇을 위해 살 것인가?’의 문제이다. 그리고 인간의 삶에서 가장 중요한 것은 자기 자신이다. 세상 그 어떤 존재보다 중요하고, 산다는 것은 ‘나’라는 존재의 의미를 알아가고, ‘나’라는 존재의 흔적을 남기는 치열한 과정이다. 그럼에도 불구하고 대부분의 사람들은 정작 중요한 숙제는 제쳐두고 눈앞에 닥친 현실적인 문제에 전전긍긍하며 살아간다.

세상살이 중 상처받지 않고 절망해 보지 않은 사람은 드물다. 목표하는 바를 이루지 못하고 사회와 세상에서 버림받고 상처 받은 사람들 투성이다. 하지만 절망 안에 머물러만 있다면, 영혼의 실패자가 될 것이다. 이매리의 작품은 상처 입은 자들에 대한 진혼이자 아픔을 극복하기 위한 자기치유의 발로이다. 세속적 의미의 성공만이 최선이 아니라 자신을 돌아보고 주위를 돌아보면 나를 존재하게 해준 수많은 사람과 역사에 감사하는 마음이 생긴다. 나라는 존재가 있기까지 나를 사랑해주고 나를 지탱해준 수많은 사람들과 유무형의 수많은 관계들을 발견할 수 있다. 작가 이매리에게 부모와 조상, 가족 그리고 친구들이 그 대상이고, 고향과 같이 나를 지켜봐주고 나를 품어준 장소나 공간이 그러한 존재들이다.

작품과 작가의 나이가 무슨 상관이 있겠냐 싶겠지만, 작가 이매리는 오십세를 넘겼다. 오십세는 흐르는 강물마냥 머무르지 못하고 쉼 없이 흘러만 가는 세월 속에서 어느덧 하늘의 뜻을 알고 하늘의 뜻에 따라 산다는 지천명의 나이라고 한다. 그러나 현실에서 오십대들은 성인이 되어가는 자식 뒷바라지와 정년을 코앞에 두고 불안하기만 한 노후대책 사이에서 팍팍한 삶을 살아간다. 그러나 그들의 가슴 한편에는 자신의 뿌리이자 안식처와 같은 대상으로서 부모와 고향에 대한 애틋한 향수가 자리 잡고 있다.

오십대들은 자연과 인간의 추억, 고향에 관한 기억을 공유한 마지막 세대일지도 모르겠다. 작가 이매리 또한 최근 몇 년 동안 지속적으로 자기 존재에 관한 고민을 하던 중 자신을 존재하게 해준 조상과 유전자에 관한 관심을 갖게 되었다. 나아가 자신의 세대가 떠나고 나면, 후손들은 어디를 보고 자신을 기억하고, 자신을 찾고 싶을 때 어디를 갈 것인가, 어디에서 위안을 얻고 어떤 기억을 더듬을 것인가에 대해 생각해 보게 되었다고 한다. 이러한 문제의식은 인간의 의식과 인식 형성에 중요한 단서가 된 특정 장소와 공간의 역사에 대한 관심으로 확장되었다. 그리고 조상들의 삶의 터전이었고 그녀의 탯자리였던 강진 월남사지 석탑과 외갓집 대나무 숲이라는 장소를 통해 자신의 존재와 실존에 관한 근원적 질문을 던지게 된 것이다.

오늘의 시대를 흔히 ‘자기 상실’의 시대라 한다. 감각과 탐욕에 길들여져 인간본성이 사라져 가는지도 모르고 사는 사람들이 태반이고, 정복하고 소유하고 과시하려는 욕구만이 넘쳐난다. 이러한 상황에서 인간은 '인간다운 자기 자신'과 '진실한 자아'를 잃어버리고 '비본래적인 자기'에로 추락해 간다. 어떻게 살아가고 행동하며 실천해야 하는지에 대한 성찰이 절대적으로 필요가 시대이다. 자기존재를 찾아간다는 건, ‘어떻게 살 것인가?’, ‘무엇을 위해 살 것인가?’의 문제와 직결되는 것으로서 궁극적으로 인생을 살아가는 태도에 관한 것이다. 이매리의 <Portraits of Shoe-우리는 어디에서 와서 어디로 가는가?>전은 한해를 마감하는 시점에서 인생에서 중요한 것이 무엇인지, 의미 있고 가치 있는 삶이 무엇인지? 스스로에게 질문하고 반성하게 한 의미 있는 시간이 되었다.

‘Where do we come from and where are we heading to?’-In the period of loss, a message of healing through self-reflection

Kim Hee Rang, Gwangju City Gallery, Curator

The exhibition of Lee Mae Ri’s <Portraits of Shoe- Where do we come from and where are we heading to?> was a exhibition uneasy to be associated with the writer, Lee Mae Ri, without her piece of stacking up too many high-heels. However, looking at the process of her work having done innumerable trials and errors such as photos, paintings, images and installations, it may not seem that strange.

In the past, Lee Mae Ri has shown the concept of existence and non-existence, being and non-being, space and time. Many consider her as a minimalist artist. However, she has showed differentiation in that she included mentalism and humanism such as aspirations and thoughts, different from post-minimalism in the West that emphasizes materialism, technology and style. Anyhow, her pieces in the past were focused on visual formativeness than the concepts, and the conceptual story was embedded behind the minimal form. However, in this exhibition, it is outstanding that the thoughts and mentions of the writer emerge in front with more detailed and direct language. She pursues a diversion to the artwork as a reflective and philosophical tool rather than her working over art as an intelligent formative produce through this exhibit. To date, she was never distracted by anything around her, but this time, she is trying to enter into the world of art, melting her life and her substantial existence, while reflecting herself.

In this exhibit, a work that has brought over bamboo forests, Wolnam Saji Stone Stone Tower into an imaging work as well as high-heels, and those having used spirit tablet made of paper used in ancestral rites in Korea with their ancestors’ names were introduced. However, we cannot but look at the clues of her works in the ‘high-heel.’

High-heels that came into being in the middle of 2000s at her works have been read as a sex symbol, especially feminism. It has been a powerful symbol in the past. She is a female artist, and the shape is high-heel, which is so vivid and stimulant red, thereby, it was highlighted as a simple and female sex symbol. Of course, I agree to those opinions. But, her high-heels are not just a sex symbol, but an object that reveals her own existence by which it can be interpreted accurately. Furthermore, it is a self-portrait of others alienated from political and social mechanism regulated by norms and orders shaped by the traditional value, or a formative bridle. Erotic red and huge high-heels represent other’s desire to enter the center of system and power, armed with splendor and coercion. High-heel, covered with this mask, has put off its clothes, and changed into a colorless heel made from a fragile papier mache. This is not a concept of sex, which is a biological and physical sex, but sex of society & culture, also the gender, which has led us to state it clearly likewise. High-heel, armed with red and industrial material in the past has turned into a colorless and flexible material, is an attempt to reveal its essence as a feeble and humane other. Free from desire and disguise, admitting the self as it is, it can console and heal itself, while suggesting the essence directly.

Last September, her work displayed at Gwangju City Gallery <General store-From the thing to the existence> exhibition was totally absent from its form to date. It is a work that has piled up colorless high-heels on the structure made, while borrowing the architectural style of European Rotunde, which was a work and a sort of requiem for sacrificed and unfair people between the gap of socially and politically unreasonable and absurd system. After then, at this exhibition, it displays a shape of randomly stacked high-heels, denying any architectural form. Some may say that it is a shape of a stone tower, but the artist has considered a grave that symbolizes other’s sacrifice.

As we have mentioned, artist Lee was endlessly concerned about her existence and existentialism for countless years through ‘the high-heel.’ This exhibition has undone that issue truly through her autobiographical material. Bamboo forests in Gangjin, her parents’ hometown and spirit tablet made of paper used in ancestral rites in Korea with the ancestors’ names used at Wolnam Saji Three Stone Tower and ancestral rites, etc., which are substantial space and object appear in the video ‘Where do we come from and where are we heading to? I/II.’ They are the works that show the meaning of their roots and those related such as home, ancestors and family, as a mean to find out their origin of existence and reflect on themselves and their relationships. Their concern over self has extended to their interest in ecological/environmental genes such as their hometowns, from which they came- the bamboo forest and Wolnam Saji Three-story Stone Tower- and ancestors. In addition, their own biographical story leaves a room to be extended to the issue of modern people and humankind that live without a soul, still uncovered.

‘Where do we come from and where are we heading to?’

This is a saying if a person has cogitated for himself over his own life. However, it is a word forgotten, because he has to struggle from his life, hard to earn money and manage his/her life or is forgotten because he has earned a competence. The most desperate assignment for humans is ‘How to live?’ or ‘For what shall we live?’ And it is he himself that is the most significant in his life. More important than any other being in the world, life is a ferocious process to leave the trace of ‘me,’ myself, knowing the meaning what I am. Nevertheless, most people leave out a really important assignment, but manage to live their lives, getting nervous of the realistic issue in front of their eyes, setting aside the really important one.

Most of the people are hurt through their course of life. There are tons and tons of them discarded and hurt from the society and world, not achieving what they desire to accomplish. However, if they stay inside the well of frustration, their soul would fall far behind. Works by artist Lee is a expression of requiem for the people hurt and self-healing to overcome their pain. A success in a secular meaning is not the best, but as you look around yourself and others, you can be grateful to so many people and history that have made yourself as who you are. So many people have loved and supported me, and there are so many relationships tangible or untangible. For artist Lee, her parents, ancestors, family and friends are the objects, and spaces or places that kept an eye on me and embraced me are those kinds of beings.

You may doubt the relationships between the work and artist, but artist Lee has passed age 50. Many people have said that 50 is an age of jicheonmyung, subject to live as the will of God and acknowledge it when the time flows endlessly, that keeps on flowing as a river. However, people in their 50s live under a great stress, unstable with their economic adversity supporting their children turning into adults. But, on one side of their heart, there is a lovely nostalgia as to their parents and hometown, which is regarded as their haven and root.

People in their 50s would be the last generation that has shared their memory for reminiscence and hometown of nature and human. Ms. Lee turned to her ancestors and genes that made her live to date, while she worried about herself endlessly for the last few years. Furthermore, she said that she came to think about some questions like, ‘If our generation leaves, where would the descendants look at and remember? ’Where would they head to when they want to see me?‘ and ’Where would they get consolation?‘ and ’Which memory would they keep in touch with?’ This kind of critical mind has extended to the interest in specific place and space that have become important clue for forming human sense and awareness, and through the places Gangjin Wolnam Saji Stone Tower and her mother’s side, base of her ancestors and her origin of birthplace, she came to cast original questions as to her existence and existentialism.

Many say that the present age is filled with ‘Loss of Self.’ Tamed with sense and voracity, there are so many people not acknowledging their human nature is disappearing, and desire to conquer, possess and show off overflows. Under this circumstance, humans have lost ‘humane and true self,’ falling down to ‘non-original self.’ Reflection over how to live, behave and practice is desperately required in this age. Seeking one’s own existence is directly connected to the issue of how I would live and for what I would live, and is ultimately concerned with the attitude of living one’s own life. Ms. Lee’s <Portraits of Shoe-Where do we come from and Where are we heading to?> exhibition was a meaningful time asking and reflecting on ‘What is important in life?’ and ‘What kind of life is meaningful and valuable?’

"......Where have you come from and where are you going?''

(GENESIS 17:8)